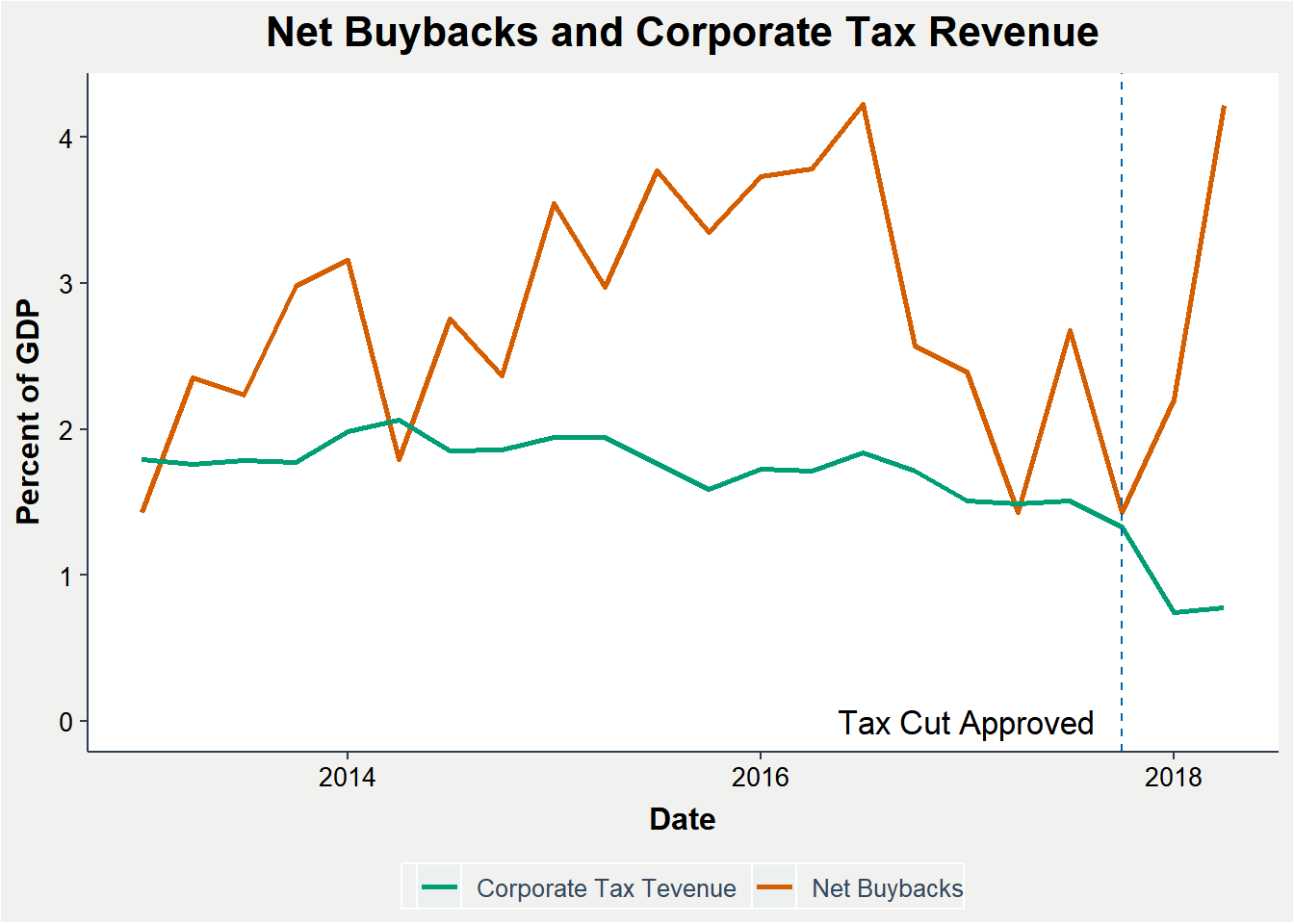

Since the Trump tax cuts were approved, there’s been an expected fall in tax revenues from corporations but there’s also been a surge in buybacks.

There are claims that companies are foregoing investment and using the extra cash to buyback their shares. Buybacks have been on the rise since they became legal in 1982 and corporate investment has been sluggish as this deloitte article explains:

The general concern is that increasing share buybacks and dividend distribution among nonfinancial corporations is coming at the cost of business investment (which, if undertaken, would lead to long-term gains in productivity and overall economic value).

A share buyback is the act of returning cash to shareholders by buying common shares held by them. Those who sell their shares will receive the cash and those who don’t sell get a larger piece of corporate profits. However, corporations may issue new shares in the same time period as they buy back shares. It’s best to look at net share buybacks as this number takes into account the amount left over for investment.

Are buybacks holding back investment?

Those who claim buybacks discourage investment point to how corporate executives are incentivised by the positive effect buybacks have on the share price. As buybacks reduce the number of shares available, this could increase the price of the remaining shares. There is evidence of this happening. But Clifford Asness et al argue this has less to do with buybacks cutting the number of shares available:

First, repurchases might signal that management believes that shares are undervalued…Second, because interest payments are tax deductible, debt financed repurchases can be viewed as good news due to the resulting lower tax burden. Third, investors may feel as though it is better for management to return excess cash to shareholders, rather than chasing less economic “pet” projects. This kind of agency cost is often characterized as “empire building,” and avoiding it has long been viewed as one of the benefits of returning cash to shareholders.

If buybacks don’t deter investment through the lure of higher share prices, then they may do so through the lure of higher earnings per share (EPS):

Basically, earnings per share are earnings divided by the number of shares outstanding. So, as a company’s earnings decrease, management is able to lessen the blow on a per-share basis by reducing the share count through buybacks. As revenue and earnings deteriorate, the buybacks bolster the EPS.

However, buybacks don’t just affect the number of shares outstanding as cash is used to buy back those shares and that cash may have had better uses. Here’s Clifford Asness and co explaining how buybacks wouldn’t boost EPS in the long run:

The problem with this argument is that it ignores the fact that decreased cash means lower earnings, either due to less interest earned on the cash or the loss of returns from other uses of the cash. Only if the cash that is used for share repurchases is truly idle (sitting in the Chairman’s desk drawer) would we agree that share repurchases increase EPS.

A point this Mckinsey article supports:

The idea that share repurchases create value by increasing EPS also errs in its failure to consider other possible uses of the cash, such as paying dividends, repaying debt, increasing cash balances, or investing in new growth opportunities.

In the short term, buybacks can artificially raise EPS and corporate executives whose compensation is based on stock options will have an incentive to do this as Clifford Asness et al recognize:

As discussed in myth 4, share repurchases should not increase EPS over time. However, a carefully timed share repurchase, just ahead of an earnings announcement, can reduce share count and thus mechanically increase earnings per share relative to what it would have been absent the repurchase.

There’s evidence which suggests incentives could be skewed in S&P500 companies:

Consider the 10 largest repurchasers, which spent a combined $859 billion on buybacks, an amount equal to 68% of their combined net income, from 2003 through 2012. During the same decade, their CEOs received, on average, a total of $168 million each in compensation. On average, 34% of their compensation was in the form of stock options and 24% in stock awards. At these companies the next four highest-paid senior executives each received, on average, $77 million in compensation during the 10 years—27% of it in stock options and 29% in stock awards.

But a solution exists:

If this is an issue, a simple solution would be modification of compensation contracts to adjust EPS growth for repurchase effects, akin to adjustments often made for dividend decisions in the context of employee share options.

In theory, an investment should be made if its expected return exceeds the hurdle rate. With cash not being the only source of funds, less cash being made available because of buybacks shouldn’t stop a potential profitable investment from happening.

What could discourage investment is that the benefits are realised in the long run and the Mckinsey reports shows that buybacks are more lucrative in the short run.

In this simple example, we’ve assumed that the company earned an immediate 15 percent return on its investment. That’s often not realistic, since there will be a lag between when a company invests and when it realizes a return. For example, if the company didn’t earn a return until year three, its EPS for the first two years would be higher from share repurchases than it would be from investing. This explains the temptation to repurchase shares instead of investing. With a share repurchase, the effect on EPS is immediate, and with investing, it is delayed.

The longer the time period, the riskier the venture becomes. An investment which looked profitable at the time may turn out to be a loss maker. Capital expenditure needs to be planned before it’s undertaken and so we may see a rise in the future owing to the Trump tax cuts but a possible trade war doesn’t help. One driver of expected return is future demand and as Oxford University’s Simon Wren-Lewis explains, firms are unlikely to make investments today if demand isn’t expected to expand tomorrow.

So, companies could be giving back money to shareholders because of a lack of profitable projects to invest in. This may be bad for individual companies and shareholders but this may not be a bad thing for the economy as a whole as John Cochrane explains:

If company 1 doesn’t have any good investment ideas, even after the tax cut, and company 2 does have some good investment ideas, made better after the tax cut, the economy needs to get money from company 1 to company 2. Company 1 could buy company 2; company 1 could invest in company 2 by buying its stock or buying its debt (all that “cash” you hear about); company 1 could return money to shareholders, and the shareholders could invest in company 2. They’re all the same, to economics. Of all the ways to do this, actually, the last might well be the most efficient. Shareholders might have better ideas about good investments than managers of a company that doesn’t have any good investment ideas.

While the lure of higher EPS or share prices may compete with investment decisions in the short term, a good counterfactual to all of this would be to look at whether investment decisions would be the same if buybacks were not possible.